Accepting design

How can we redefine our expectations to match our purpose?

Written by

Caio Braga,

Fabricio Teixeira

Art Direction by

Manoel do Amaral

Of promised lands and broken hearts

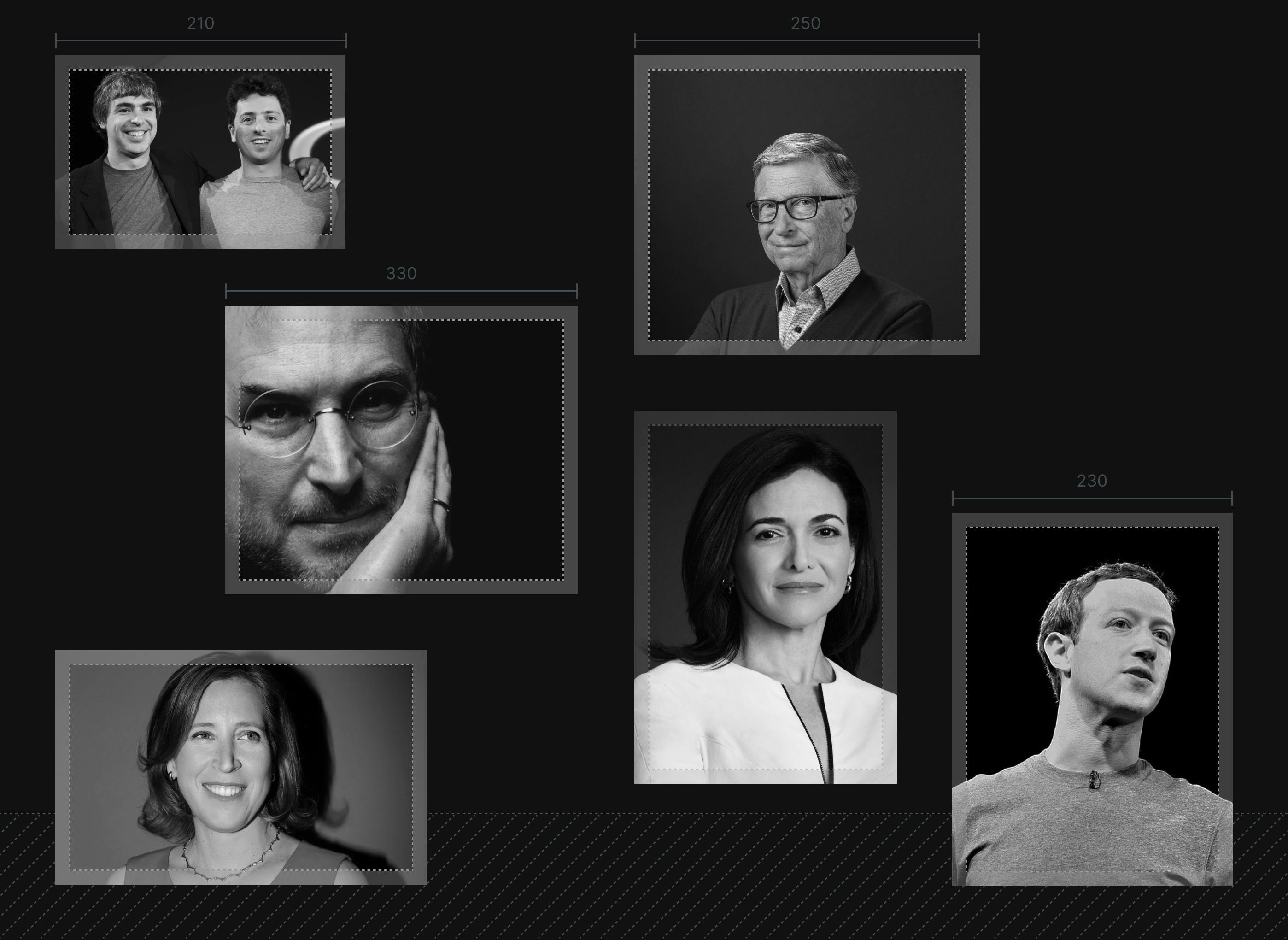

Two decades ago, designers from all corners of the world were captivated by a simple, unifying vision: the internet’s immense potential to connect individuals and to provide access to information, entertainment, and services to everyone. It all felt like a higher calling; all stars aligned to create a limitless universe for exploration. In the years that followed, many of us embraced this visionary outlook and decided to become the designers of these new digital platforms.

It didn’t feel like we were joining an industry, a career, or a job, for that matter.

It felt like we were joining something bigger than ourselves.

We looked up to the pioneers who embodied the epitome of digital leadership. We saw ourselves in them, projecting our aspirations onto those individuals who had successfully navigated the uncertain terrain of innovation and emerged as leaders. We sought to emulate their ingenuity, creativity, and entrepreneurial spirit, believing that by doing so, we could also help shape the future of the internet and “leave a little dent in the universe.”

“At Apple, people are putting in 18-hour days. We attract a different type of person—a person who doesn’t want to wait five or ten years to have someone take a giant risk on him or her. Someone who really wants to get in a little over his head and make a little dent in the universe.”

—Steve Jobs talking about the type of talent he was looking for at Apple

None of those big tech idols were designers by trade, but we took the bait anyways: we fetishized the role of design (and the designer) in all this.

Some of us did put in 18-hour days to make that happen.

And the motto of moving fast and breaking things, coined by Facebook but followed by every other company in that same era… well… did end up breaking things. Social networks, designed for “engagement,” have transformed from global connectors to platforms rife with misinformation and shallow content. Digital banks make grand promises of “bringing access to financial services to excluded populations” but employ deceptive UX tactics to convert more users.

At some point, those same designers from all corners of the world finally came to the unpleasant realization that design, in corporate settings, is just another investment to grow businesses.

Mark Zuckerberg testifying in court

Are designers even able to influence anything?

As our romanticized view of the industry started to fade, these types of questions became inevitable. Isn’t ultimately money what’s informing the decisions that will shape these products? Although designers have some degree of influence over the user experience, we understand that our power is limited to the how, not necessarily the what, why, or how much.

Think about the addictive nature of products like TikTok or the negative impact of Instagram on teenage self-esteem. While designers can certainly create features to mitigate some of these issues, the question remains: can design fundamentally alter the underlying incentives that drive the development of these platforms?

Some argue that influence is gradually diminishing, especially now that larger tech companies are entering what is defined by Tim Carmody as their “decline phase.” The term refers to a stage in the lifecycle of big tech where their innovation start to stagnate or diminish, often linked to these companies’ inability to adapt to changes in the market, as well as the inherent challenges of scaling beyond their original vision.

Tangibly, this decline leads to a shift in priorities, including within design teams. For a long time, investing in design meant investing in R&D and innovation, terms that resonated well with investors and venture capitalists while the market was expanding and making new, bold bets on this promising future. But as these companies switched their focus to profitability and optimization, design moved further away from the core of their business.

Maybe we've been overestimating our power as designers all this time.

Or maybe our power lies somewhere else.

Designers who design, bakers who bake

“With the advent of industrialization, furniture-making became a factory-line process. This meant that more furniture could be produced for less, making it more accessible to a wider range of people. Instead of furniture makers designing chairs, a smaller number of industrial designers working for furniture brands like Knoll, Habitat, and later IKEA created the designs, and large factories populated by lower-skilled workers produced them en masse. Although there is still a need for furniture makers, especially at the high end, the number of local furniture makers has dropped significantly. The same fate may await the design industry.” (Andy Budd, The end of design as we know it?)

A lot of product designers out there share an appreciation for other hands-on, craft-based activities. Some even dream of switching careers to become furniture makers, leather artists, pottery experts, or pâtissiers: waking up early to do what they enjoy, putting in the time to master the craft, and learning to appreciate the process as much as the output. Then starting over every single day. And being ok with that idea.

Why can't we be ok when it comes to digital product design?

As designers become more cynical about their impact and the future of Tech, lies an excellent opportunity to reflect and understand what really motivates us: What do we really appreciate about design? Why are we here? Why now?

It was easier to ignore these questions when designers were growing in their careers and unlocking opportunities everywhere. For many with the privilege of working in Big Tech for the past decade, it was a matter of taking a deep breath while they fantasized about a different career without the stress, politics, and Kafkaesque ambiguity of big corporations.

When all that Big Tech energy starts to dissipate, we find ourselves standing before the mirror, heart pounding, confronted with the only question left for us: Are we willing to accept design?

Other types of designers have fully embraced their discipline for what it is. Good furniture designers will design chairs that are both beautiful and usable—perfectly balancing form and function. Great designers will design chairs that are unique, memorable, and work particularly well for certain environments. Thoughtful designers will consider materials, sustainability, ergonomy, and many other factors that will make a positive impact beyond the chair itself.

None of these designers have ambitions to change the world with just a chair — but they can definitely find joy in that process. How might we redefine our expectations to make sure the work we do aligns with our purpose?

01

Finding joy in our craft

There has been a long-standing disdain for manual work and craft in our society, perpetuated by the bourgeois idea that the only valuable form of capital is intellectual. But isn’t craft what brings us the most joy as designers?

Think about that feeling when the perfect color or font combination just feels right. Or when that first draft of an idea comes together into a prototype. When we watch users interact with our design and see it having a positive impact on their experience. Solving a particularly challenging design problem and feeling a sense of satisfaction. Discovering a new trick that will make our workflow more efficient. Collaborating with other designers, feeling inspired by their creativity. Finding inspiration from other places and industries and incorporating those references into our work.

Are we able to enjoy our process as much as the outcome of our work?

02

Impact is impact — at any scale

You don’t need to design a product for 2 billion people for it to be a successful product or for you to be a successful designer. Working in big corporations is not the only way.

In fact, there are more design opportunities, in smaller, underserved sectors. You can strive for high impact on a local business. Or with a niched audience. You can specialize in designing a pretty specific type of experience. Aim to meaningfully change one person’s life versus creating a suboptimal product that tries to serve every human on Earth.

How can we start thinking about our career beyond Big Tech and our value beyond big numbers—and focus on becoming a better designer every day?

03

It’s ok to work for money

Money is a necessary part of our lives: we want to pursue our passions, but we also need to survive, support our families, and our needs. Charging for our time and work product doesn't make us greedy or selfish. It's a fair exchange of value.

With very few exceptions, every company, brand, or organization's goals revolve around money— and it’s likely that your design will help them reach those goals. Our personal goals, however, might go beyond making money. Deliver great work to make an impact for your employer, but do not expect your job to be the only thing that fulfills you in life.

Define who you want to be as a person, set the proper boundaries with your work, and don’t forget to send them the invoice.

04

Accepting change

Humans will always try to automate repetitive tasks. Think about mass manufacturing before assembly lines, or accounting before spreadsheet software. Automation will always change what’s expected from jobs.

Design is not any different. The concept of being a designer (and the types of tasks we do every day) changes every couple of years. That has always been the case. With AI, our job is changing again—hopefully, renaming layers will be a thing of the past.

A curious mindset is a big part of being a designer. This feels like a great time to learn new things as we define what's next.

05

People are the real legacy

We are designing interfaces that last a few years in their current form; if all stars align, they might last a few more. We’re in such a nascent industry that our concept of “long-term” is quite open to interpretation.

Projects change, products get redesigned, jobs come and go. But people, and the relationships they build, stay. The ideas we share, the values we spread, or how much we help others learn and grow in their craft — that is the legacy that goes beyond the products we put out.

We should be paying attention to our values and how they influence our colleagues as much as we do to our outputs and how they influence our end-users.

As designers are revisiting the role they want to be playing in the world and questioning where we can go from here as a profession, the answer might be more obvious than we all want it to be: learning to separate the craft of making digital products from the industry we’re in.

Works Cited

- New study identifies ‘TikTok addiction’ by Adam Smith

- Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic by Wells, Horwitz, Seetharaman

- Two ways to think about decline by Tim Carmody

- The end of design as we know it? By Andy Budd