Returning to craft

How returning to the craft taught me to be a better leader

Written by

Aly Blenkin

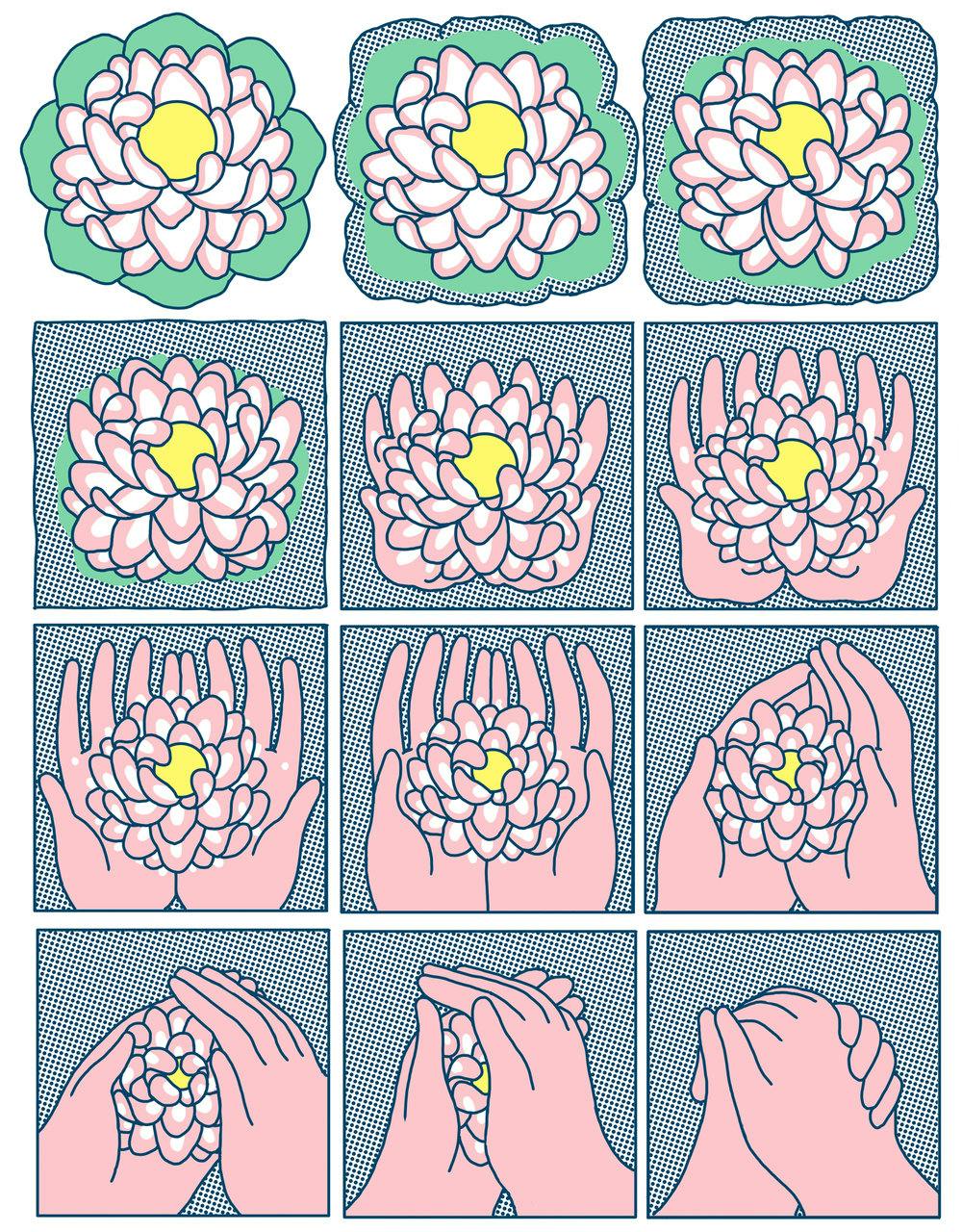

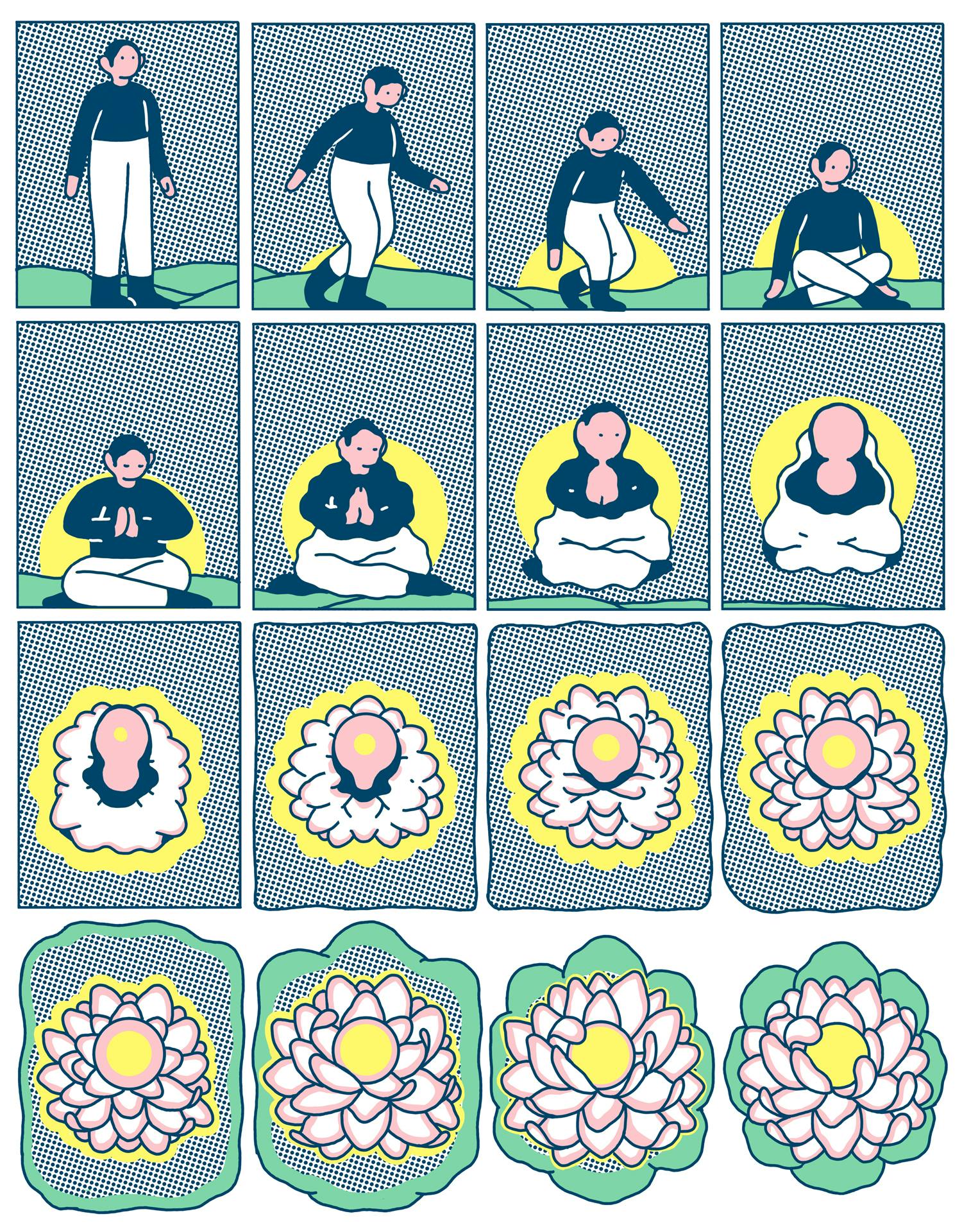

Illustrations from the book "Focus" by Evan M. Cohen

I recently made a few "fresh starts" in my life; moving countries and changing roles in my career were two of the most significant. With my job, I decided to move away from design leadership and return to being a product designer. However, I didn't anticipate that going back to the craft would also teach me to be a better leader.

I went back to the craft because I missed delivering products and services for people. The transition away from management (where I mainly designed slide decks) back to designing products wasn't an easy switch; many of the tools and practices have changed over the years. For a while, I asked myself daily if I still “had it", whatever exactly "it" is.

In sharing my reflections and learnings, I hope to spark a bit of curiosity in others, so they too might play with the idea of practicing again.

Your technical skills don't disappear; they morph as you grow in other areas.

Recognizing knowledge gaps

First off, your technical skills don't disappear; they morph as you grow in other areas. When you move into a leadership role, the scale in which you interact with problems shifts.

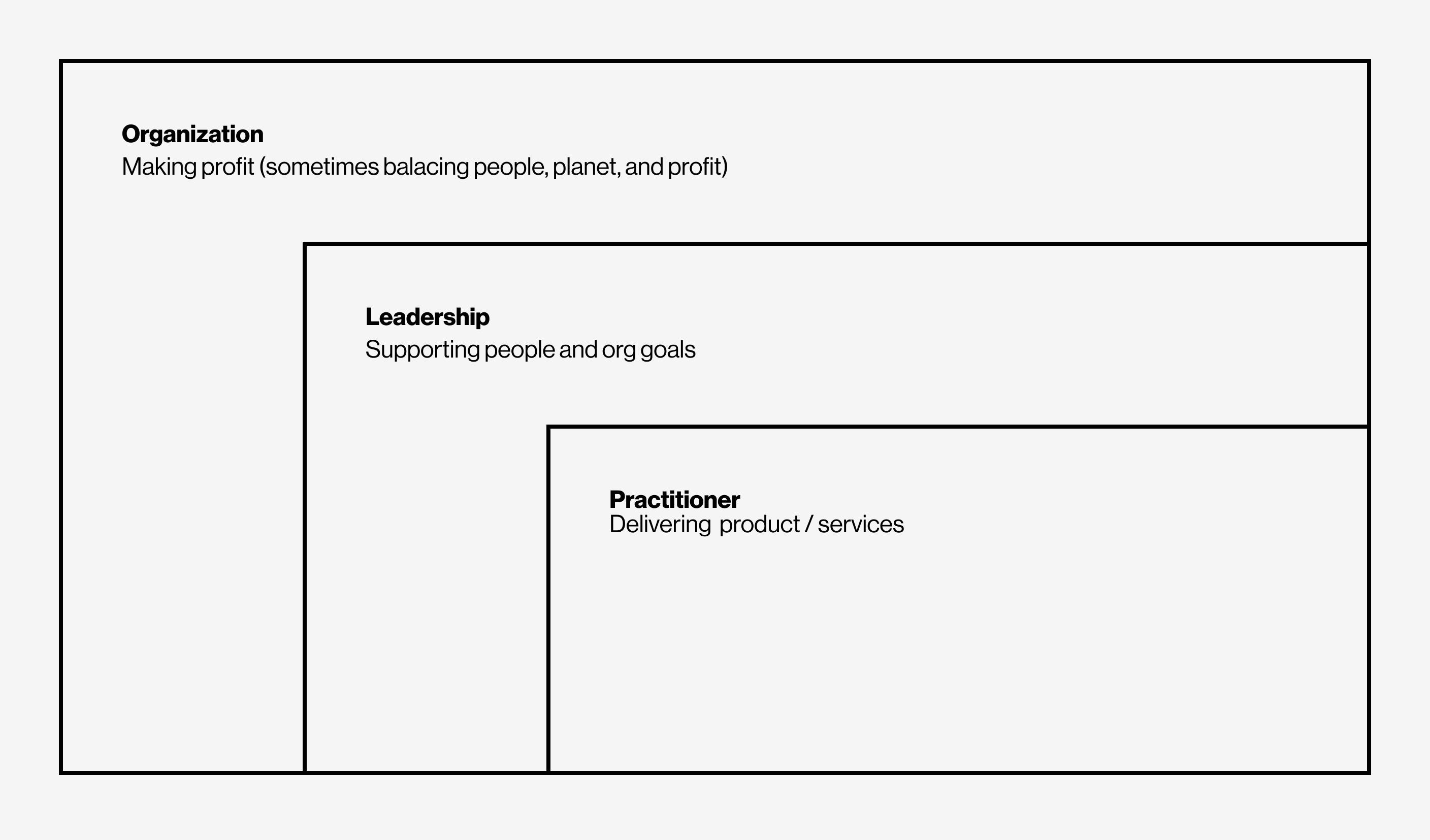

As a practitioner, you address mostly product-level problems, being responsible to define a customer experience that delivers on the overall strategy. Whereas for a leadership role, the focus shifts to higher-level strategic decisions and supporting their teams to execute on it. Going back to delivering the work requires an entirely different mindset, and it isn't easy to switch off the management tendencies.

I genuinely enjoy managing and creating scaffolding for teams to do their best work. However, over the past few years, I've had this lingering feeling that I need to better understand what it takes to deliver products and services in the current environment to show up as an authentic leader. The higher the level of the manager, the harder it is for them to stay on top of all the new tools and practices needed to deliver on a space that is constantly evolving. As a result, leadership practitioner skills naturally depreciate over time.

By focusing on the bigger picture, a manager might also miss the intricacies of how their product actually works. As digital products become more sophisticated, understanding the trade-offs, complexities, and dependencies. As Rochelle Gold articulates in their article, it's a risk when there is a gap between where decisions are made and what happens on the ground.

“When there is too much distance between where decisions are made and the day-to-day delivery, we risk not understanding what is truly needed.” Rochelle Gold, Head of User Research, NHS Digital

Beyond the tooling and capabilities, our field also matured on how to better serve the users impacted by our products. There are simply better ways to design, build, and manage services for the business and for the customers: design justice, equity, ethics and bias in tech, accessibility, disrupting power, liberating technology from capitalism, and trauma-informed design are just some examples.

Understanding each of these areas theoretically is different from actively reflecting and applying learnings in practice. As a manager, it’s one thing to speak about what we should or shouldn’t do and another to know what it takes to implement and deliver the work. For example, I’ve talked about why designing responsible technology is essential, but I hadn’t designed a product or service in years so it felt removed. I wanted to be grounded in the craft to better understand how to build responsible technology in today’s environment.

It's a pendulum: from management back to practice

Charity Majors, co-founder and CTO of Honeycomb, writes about the individual contributor and management pendulum. Specifically, the breadth and strength that accrues to practitioners that go back and forth between the two:

“The best frontline engineer managers in the world are the ones that are never more than 2–3 years removed from hands-on work, full time down in the trenches. The best individual contributors are the ones who have done time in management. And the best technical leaders in the world are often the ones who do both. Back and forth. Like a pendulum.”

Going back to the practice was an exciting opportunity to grow and sharpen my skills. However, I was out of practice as a product designer for about four years, so the learning curve was high. I knew there would be a significant amount of relearning and unlearning that I would need to do. A pendulum approach to team management and to your career can be a great way to keep growing as a designer and for the team to deliver their best work.

Re/unlearning the tools

Even with my disciplined approach to documenting learnings, some of my skills were utterly dormant, so it took hard work to get up to speed again.

Illustrations from the book "Focus" by Evan M. Cohen

There was also a massive shift in my day-to-day activities. No more back-to-back meetings, from 1:1 coaching to recruiting or managing stakeholders. The context switching as a manager left me in this perpetual state of feeling behind. Going back to the practice didn't remove that pressure; the intensity of the work became more focused and less scattered.

As a practitioner, you’re accountable for producing the work, despite how rusty you might feel. You’re responsible for clearly articulating what needs to get done and then doing it. It took constant self-encouragement to push through doubting my abilities.

“Practice is betting on myself: It’s being brave enough to be a beginner at something, and loving enough that I let go of the shame, rushedness and defeatism that makes practice unsustainable.” — Annika is Dreaming

In the beginning, I felt like I was constantly unlearning and relearning on the fly. Cyndi Suarez, the author of The Power Manual, writes about the "learning edge," or learning outside of your comfort zone, where you leave behind old identities and practices that no longer serve you or others.

It's easy for leadership to forget what it feels like to deliver a live product or service. When I was in a management role, I sometimes found myself slipping into this mindset of I've "been-there-done-that" type of thinking. Seeing things from both viewpoints expanded my empathy. I understand the pressures leadership need to manage. Equally, going back to the craft also restored my empathy for practitioners, and my energy to learn as if I was seeing things for the first time.

Becoming a better leader by becoming a better designer

Learning product design tools and practices again made me look at management differently. It made me think of how I can better support people.

Illustrations from the book "Focus" by Evan M. Cohen

1. Slowing down to reflect and grow as a team

There is a lot of pressure to rapidly-produce work and not enough time to learn. From a business perspective, there are always competing pressures; teams are hyper-productive or underutilized for taking time for personal development. The value of learning and growing as a team often isn't considered a worthwhile investment for both practitioners and managers.

What would it look like if we spent more time fostering spaces to grow as a team?

HmntyCntrd is modeling what it looks like for a company to slow down to reflect meaningfully. At their conference in 2021, founder Vivianne Castillo said, "We believe rest is a form of resistance." Everyone at HmntyCntrd spent the last 45 days of the year not taking on any new clients or consulting work. Instead, they took time to rest, read, create and breathe.

2. Creating an environment to challenge "best practices"

What once was the best practice may not be relevant or appropriate anymore. Moving fast and delivering work at any expense or without regard for consequences no longer works, and it never did.

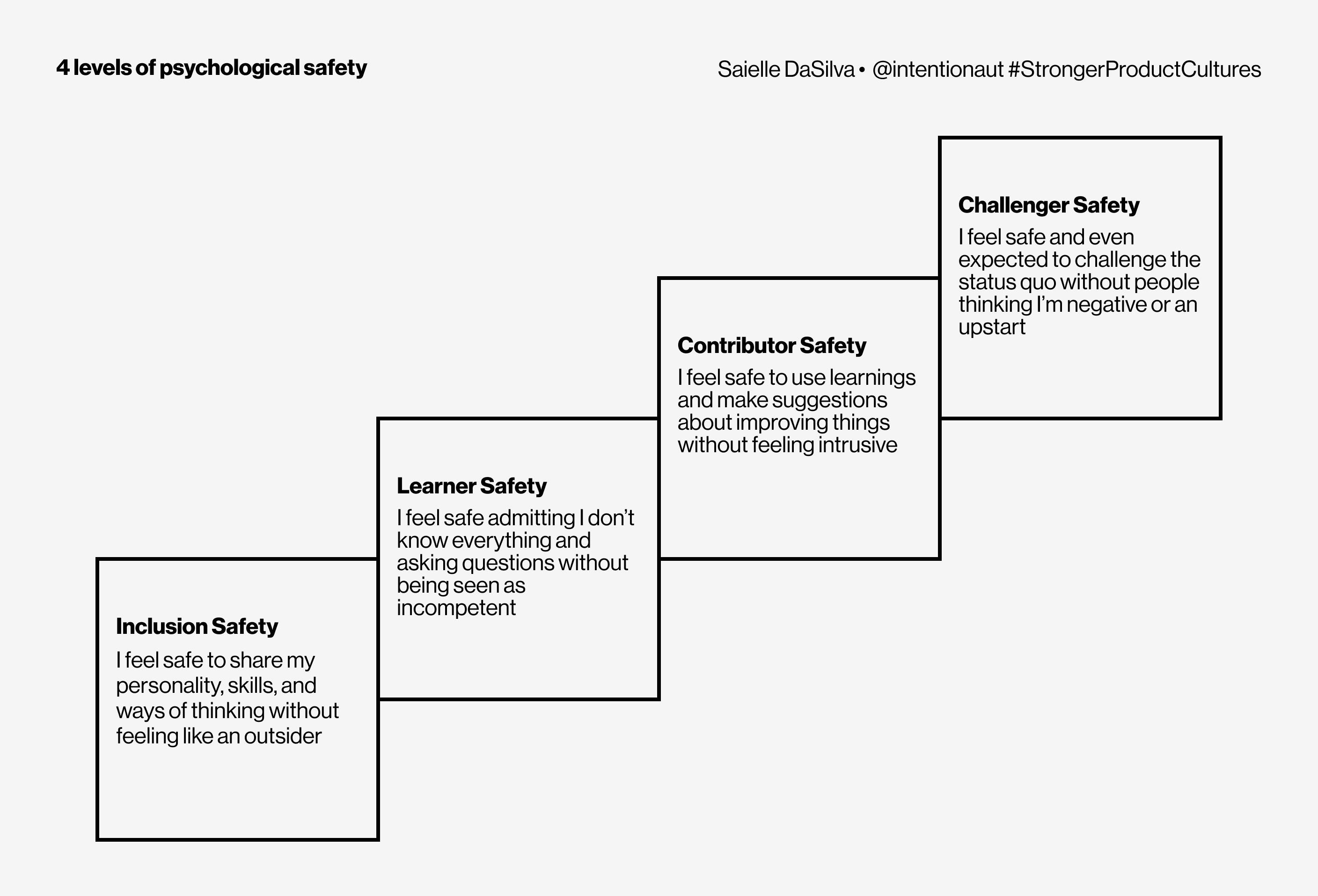

Healthy work cultures are built in environments where it's safe to challenge and contribute. I saw this image of Saielle DaSilva speaking about the importance of psychological safety — highlighting four levels of maturity for stronger product culture: Inclusion, Learner, Contributor, and Challenger Safety.

Being a designer again, I was reminded of what it feels like to challenge best practices when using a design system that wasn't fit for purpose. Questioning design patterns or mental models that are not working requires reflection and a safe environment to explore other options.

It can be vulnerable to step back and apply a learning mindset as a leader. However, the reward of making space to challenge best practices, or models that no longer serve the team, outweighs the fear of potentially feeling exposed. More importantly, modelling critical reflection as a leader fosters a "learner approach" to addressing problems, which can also start to dismantle unhelpful power structures.

3. Listening first before giving your opinion

I don’t know very many people that enjoy being micromanaged or told how to do things. The feeling of not fully being trusted impacts the team's overall health. It also reinforces practitioners to do what they think is expected rather than what is best for the work or team.

It's easy to swoop in as a leader and give your opinion on how to handle a particular challenge before giving others the space to share their views. It's probably more time-efficient, too, when you've done something so many times before and know how to handle it.

Looking back, I wonder what learning opportunities I took away from others figuring out on their own? Or how I might have created a dynamic where people didn’t think I trusted their abilities.

Continuing to experiment and wander

Exploring the design practice again has also given me the space to figure out what I want to spend my time on, reflecting on what brings me joy and allows me to be creative. It also helps me determine my boundaries on what I'm willing to fight for, grounded in current practice.

There are very few roles that give space to managers who want to explore going back to the craft. There are distinct phases that most practitioners experience in their careers. It's like once you're on the management track, you can't get off. I particularly like the approach Charity Majors takes: “Flip the idea you have to choose a ‘lane’ and grow old there. I completely reject this kind of slotting.”

Illustrations from the book "Focus" by Evan M. Cohen

There is so much value in wandering outside your lane and experimenting to expand your thinking. The longer you're away from delivering the work, the further you remove yourself from the realities of designing and building products. I wonder how much could be gained from a multidisciplinary leadership team rooted in today’s practices?

I would love to see moving back and again from being a manager and being a contributor more common and accepted in our industry. I would love to see companies taking that into consideration in their career ladders, so a manager could go back to the craft without feeling they are moving backwards in their careers or closing a doo for their future.

As this beautiful quote from Helen Tran says:

“Beginners, don’t lose your mind. Veterans, don’t lose your edge.”

Finding common threads

Hearing about similar transitions is yet not too common - most content, guides, and even mentorships are framed around becoming a manager or growing as an individual contributor.

I would love to hear more from folks in similar transitions - share your stories, your perspectives, and your learnings. Those who are considering changing tracks: reflect on what you expect from your next career move and how you plan to keep in touch with your practice that made you a designer in the first place. Your career is not made of linear, premeditated steps, so don't limit it by what is said out there. Shape your career on learning and moving forward toward what you want to do in this world.

Acknowledgments

Shout out to Lucy Stewart, Emma Parnel, and Alessandra Canella for our wandering chats about the ups and downs of freelance and going back to the craft.

Works cited

- How NHS Digital is developing user-centred design maturity by Rochelle Gold

- The engineer/manager pendulum by Charity Majors

- The Power Manual by Cyndi Suarez

- HmntyCntrd Critical UX Conference 2021 by Vivianne Castillo

- Jackie Bavaro on Twitter

- Hot Streaks in Your Career Don’t Happen by Accident by Derek Thompson

- Helen Tran on Twitter

- Focus by Evan M. Cohen