Lenses to peek into the metaverse

Written by

Karina Nguyen

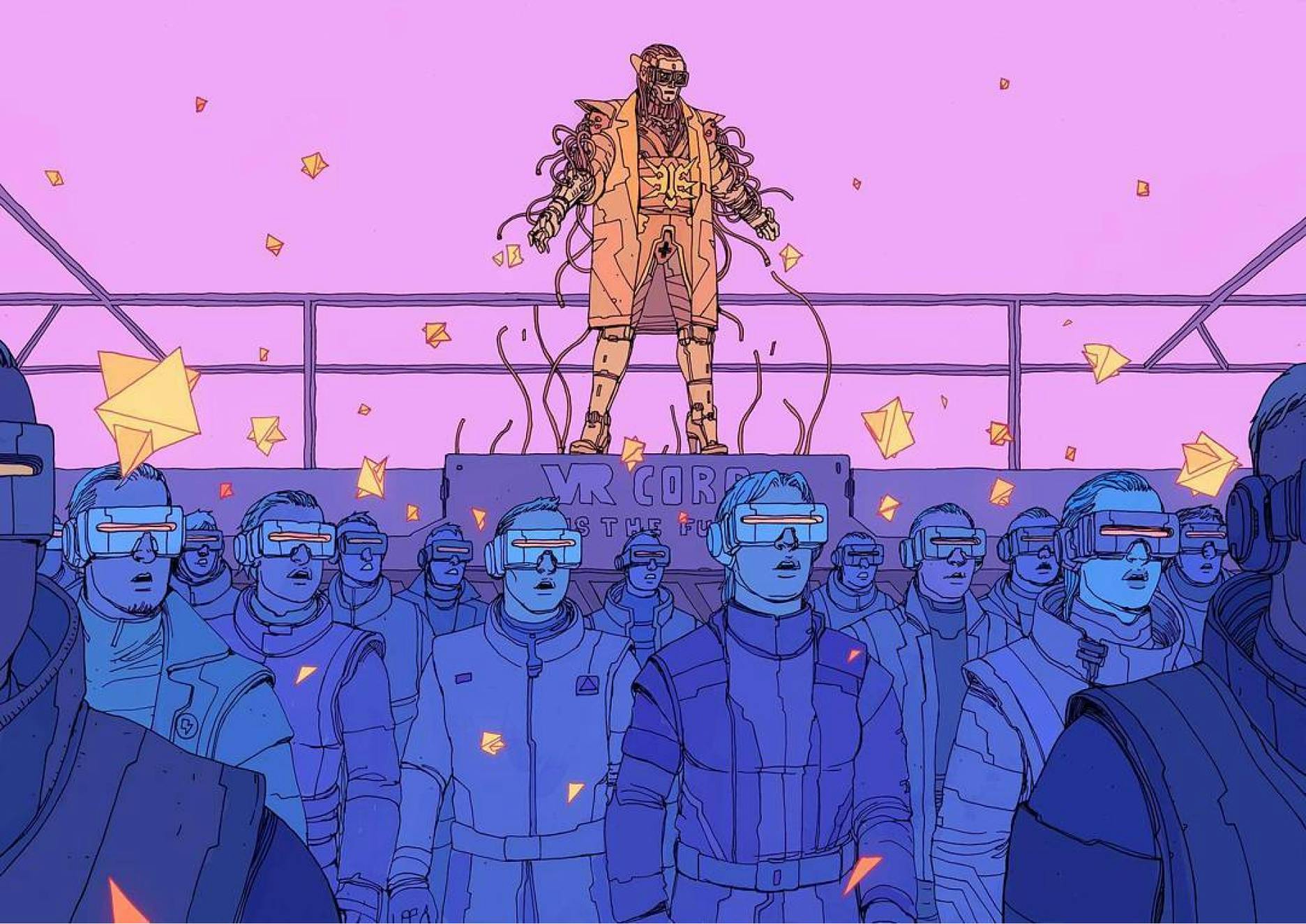

Illustrations by deathburger

The virtual reality space is far from being exempt from risks to our society. Peeking into it through philosophical, technological, ethical, and cognitive lenses can help designers and engineers be aware of the risks and traumas it can cause.

Illustrations by deathburger

Philosophical lens:

Humans are imitative. Virtual reality fits the bill.

Plato’s Republic, one of the philosopher’s earliest works, posits the idea that art is imitative. Plato utilized this theory to dismiss art as being secondary or derivative, but also to suggest that because art imitates life, life also imitates art, in so far as we mirror the emotions of characters on stage.

Aristotle, Plato’s student, argued against this idea in his Poetics. He suggested that art was a venue wherein people can experience in a controlled way potentially overwhelming emotions, and learn thereby to gain better control over these emotions.

“Tragedy: a representation of an action that is heroic and complete and of a certain magnitude — by means of language enriched with all kinds of ornament, each used separately in the different parts of the play: it represents men in action and does not use narrative, and through pity and fear it effects relief to these and similar emotions.” (Aristotle)

So we see here two opposing views from the ancients on the relationship between art, emotion, and ethics. In the nineteenth century, inspired by the moral philosophy of Adam Smith, the novelist George Eliot offered a slightly different view for how art can affect our feelings and therefore our social relationships:

“The greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet, or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies…. a picture of human life such as a great artist can give, surprises even the trivial and the selfish into that attention to what is apart from themselves, which may be called the raw material of moral sentiment… Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.”

This theory suggests that these emotions bring us closer to others, makes us sympathize with them. I would argue that Eliot’s idea about what art is for, emotionally and socially, is still very prominent in our era, though we are much more likely to make the argument about novels than about video games.

Brecht found in Chinese acting a model of self-conscious, meta-artistic art that might interrupt the imitative tendency of the theater. He suggests that “the transference of these emotions to the spectator, the emotional contagion, does not take place automatically.” So the alienation effect keeps us from emotional immersion and contagion and therefore allows us to think and critique society.

Because each of these theories is grounded in the question of art as a technology of imitation, you might note that the central concerns in each are exacerbated that more realistic art becomes. On one hand, this is about realism — how close to reality does this art seem? On the other hand, this is about the experience — how similar to the experience of life is my engagement with this art?

Virtual reality and the metaverse are no different.

Illustrations by deathburger

Technological lens:

Mirror, theatre, video game.

It’s, therefore, no surprise that virtual reality is plagued with the same opposing views about its effects. In the movie Matrix, virtual reality is compared to a mirror. In Striking Vipers (Netflix Black Mirror), we see it as the mechanism to play a video game, in its literal definition.

Virtual reality is like mimesis in its focus on imitating life; it is like the theatre and the game in its interactive engagement. Its aim is to create a version of reality that sheds its frame, is unmediated.

The ‘virtual reality effect’ is the denial of the role of signs (bits, pixels, and binary codes) in the production of what the user experiences are as unmediated presence. This requires the disappearance of the computer and of language itself.

Joshua Rothman’s New Yorker essay “Are We Already Living in Virtual Reality?”, is about the next frontier in the virtual reality effect, toward less mediation or rather, toward greater inhabitation. It entails, as much of Rothman’s work for the New Yorker does, a combination of a profile — usually of one or more professors in philosophy or cognitive science — and a meditation on the implications of their research. Rothman uses, throughout his piece, analogies to the various artistic media.

He discusses “a tracking hardware which allows your virtual body to accurately mirror the movements of your real head, feet, and hands — and a few minutes of guided, Tai Chi-like movement before a virtual mirror” (the technology also frequently uses mirrors). The obsession with the “out of body experience” that leads the main subject of the piece, the philosopher of mind Thomas Metzinger, to develop virtual embodiment is compared to a theatrical stage set:

“In 1983, the psychologist Philip Johnson-Laird had published a book called ‘Mental Models,’ in which he argued that people often think not by applying logical rules but by manipulating models of the world in their minds…. Reality, as do we experience it, might be a mental stage set — a representation of the world, rather than the world itself. Metzinger started to think about how such a model might be constructed. Some internal mental system must function as an invisible, unconscious set dresser.”

In the memoir ‘Dawn of the New Everything,’ the V.R. pioneer Jaron Lanier recalls evangelizing the technology by describing a virtual two-hundred-foot-tall amethyst octopus with an opening in its head; inside would be a furry cave with a bed that hugs you while you sleep. Later, the ‘Matrix’ movies imagined a virtual world so accurate as to be indistinguishable from real life. Today’s most advanced V.R. video games conjure visually rich space stations (Lone Echo), deserts (Arizona Sunshine), and rock faces (The Climb). The goal is to convince you that you are somewhere else.

These three technological and artistic analogies — mirror, theatre, video game — once again ground Rothman’s analysis of virtual reality and emphasize its mimetic and experiential affordances. And once again, the spectre of how those affordances might affect society, emotionally and ethically, hovers over the essay.

Illustrations by deathburger

Ethical lens:

Why do we need a code of ethics for VR?

Although Virtual Reality has been around in more or less the form it is now for thirty, forty years, with head-mounted displays, and so forth, there’s nobody who’s spent hours and hours, week after week, month after month, in virtual reality.

When that happens, we should be prepared. As Rothman puts it: ‘There’s going to be a moral panic around V.R. as it spreads and spreads, just as there was with comics, with television. It’s going to be the root of every evil, and there’s going to be a huge campaign against it. I hope the companies realize this, because they have to be prepared for it.’

In their V.R. code of ethics, Metzinger and Madary predict that the ‘risk of users suffering psychological trauma will steadily increase as V.R. technology advances.’ Metzinger worries about scenarios that encourage the character traits that psychologists refer to as “the dark triad”: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy.”

This V.R. code of ethics is necessary because of the widespread panic that video games habituate people — especially young disaffected men — to commit acts of violence and cruelty. Anna Anthropy’s optimism in the Rise of the Videogame Zinesters (a book I highly recommend reading!) about the hacking of video games must be contrasted with its darker uses, as in the video game Grand Theft Auto, which gamers hacked in order to allow their avatars to sexually assault the avatars of other players in the game. Rothman gives an example of how some games — many games — in fact, build this violence in, no hacking necessary: In 2015, the video-game company Capcom released Kitchen, a virtual-reality horror scenario in which the player is tied to a chair while a deranged woman plunges a knife into his thigh.

In the V.R. game Surgeon Simulator, players use power drills, bone saws, and other tools to vivisect a humanoid alien that writhes in pain on the operating table. As in most V.R. video games, players in Kitchen and Surgeon Simulator move in fanciful ways and are, at best, semi-embodied. Even so, in the book ‘Experience on Demand,’ Jeremy Bailenson, a leading V.R.-embodiment researcher at Stanford, reports that after performing virtual vivisection he ‘simply felt bad. Responsible. I had used my hands to do violence.’ The first-person V.R., like the first-person shooter game, makes us not just inhabit another person, it can make us complicit with their actions.

Reproducing a feeling is independent of realism

Reproducing a feeling is independent of realism; inhabitation is far more crucial. “On some level, the brain doesn’t know the difference between real reality and virtual reality.“ Embodied simulations seem to slip beneath the cognitive threshold, affecting the associative, unconscious parts of the mind. ‘It’s directly experiential… It’s not “I know.” It’s “I am.”’ ‘It’s not real, but it doesn’t matter,’ Slater said, watching me. ‘In some sense, it’s a real experience.’ One way to put it is that virtual embodiment is not epistemological — about what we know but — phenomenological — about what we experience. And that’s what we all need to understand about the future of VR as designers, researchers, and engineers.

Illustrations by deathburger

Cognitive lens:

Not somewhere else, but someone else.

The virtual embodiment Metzinger decided to recreate intensifies this process, not by convincing you that you’re somewhere else, but by convincing “you that you are someone else. This doesn’t require fancy graphics. Instead, it calls for tracking hardware — which allows your virtual body to accurately mirror the movements of your real head, feet, and hands — and a few minutes of guided, Tai Chi-like movement before a virtual mirror.”

Rothman notes that this improves not the mimetic reality but the experiential reality of embodiment: “My virtual self didn’t feel particularly real. The quality of the virtual world was on a par with a nineteen-nineties video game, and when I leaned into the mirror to make eye contact with myself my face was planar and cartoonish.”

Du Bois may have derived this concept of double consciousness from the research of his professor, William James, the founder of modern psychology, who discussed the “Double or Secondary Personality” in his book The Principles of Psychology — a proto-theory of what we now call multiple personalities, and sometimes schizophrenia. Jung and Freud both developed this idea in their work as well, though usually in metaphoric terms.

The notion that seeing oneself from the outside will produce a remarkable shift in consciousness feels natural to us now. But virtual embodiment defamiliarizes the platitude of “getting to know yourself” — and makes it all too literal.

Virtual reality and the rise of the metaverse have a deep connection with the human imitative nature, working as a mirror for the projected ideas we have of ourselves and of our society. However, this same mirror can expose and augment problematic issues that we as designers need to be aware of to prevent and address.

Works cited:

- Virtual Reality & Bandersnatch by Namwali Serpell (2019)

- The Art of Fiction in George Eliot’s Reviews by James Rust (2021)

- Are We Already Living in Virtual Reality? by Joshua Rothman (2018)

- The Poetics of Aristotle translated by S. H. Butcher (2013)

- Cross-Cultural Encounters In World Theatre: Bertolt Brecht, The ‘Alienation’ Effect And Chinese Drama by Letizia Fusini (2018)

- Real Virtuality: A Code of Ethical Conduct. Recommendations for Good Scientific Practice and the Consumers of VR-Technology by Michael Madary and Thomas K. Metzinger (2016)

- Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality by Jaron Lanier (2018)

- Rise of the Videogame Zinesters by Anna Anthropy (2012)

- Double Consciousness by John P. Pittman (2016)

- Republic (Plato) by Wikipedia (retrieved on 2021)